Playing around with MoMA data (Part I: Mapping)

One of the datasets that I first played around with when I was sloooowly learning to use R was a really beautiful dataset that MoMA compiled and made publically available on Github, which has selected metadata on all 131,266 pieces in their permanent collection. It appealed to me because it looked like a slightly tricky dataset to work with – with variables in a lot of formats, and with kinds of data I wasn’t used to working with – but not so tricky that I wouldn’t get anywhere.

I’m mainly interested in R as a data exploration and visualization tool, since I still do much of my “serious” work in Stata. Because of this, I’ve been using the dataset as a way to experiment with different ways of visualizing data – both for myself, to understand the data better (“exploratory” visualization), and for telling a specific story to others (“explanatory” visualization). At first I thought I would just settle on one visualization, and share that here, but I actually haven’t been particularly happy with any of them. Instead, I thought what might be nice would be to do a series of posts on different ways of visualizing the same data, all motivated by the same central research question. Since this is the first one, I’m also going to share some of my struggles with manipulating the data in the first place - which might make this post a bit long, but feel free to skip to the parts that interest you the most.

I also want to acknowledge that a lot of other people have used this data to do all sorts of interesting things (and maybe the very things I’m doing here!). I’m going to try to link to them when I can, but I’m sure I’ll have missed some things; feel free to let me know if I have. So, without further ado:

The Research Question

It is I think pretty well known that many museums’ permanent collections, including MoMA’s, tend to be skewed towards ‘western’ artists, because of historical inequities in what was (or is) considered notable or worthy art (and in the case of MoMA, probably what was/is considered “modern” art. I’m by no means an art historian, but these seem like safe bets). What I’m interested in, however, is how this has shifted over time, as art trends and social contexts have changed. There’s been at least one very nice visualization that has looked at exhibitions by artist’s nation of origin over time, but I thought it would be interesting to instead look at the museum as a collector, whose permanent collection acquisitions reflect institutional priorities and larger sociopolitical trends. Luckily, the MoMA data has information for almost every piece in their permanent collection on who the artist(s) were, their countries of origin (though there were complications with this), and the date the piece was first acquired.

The Visualization

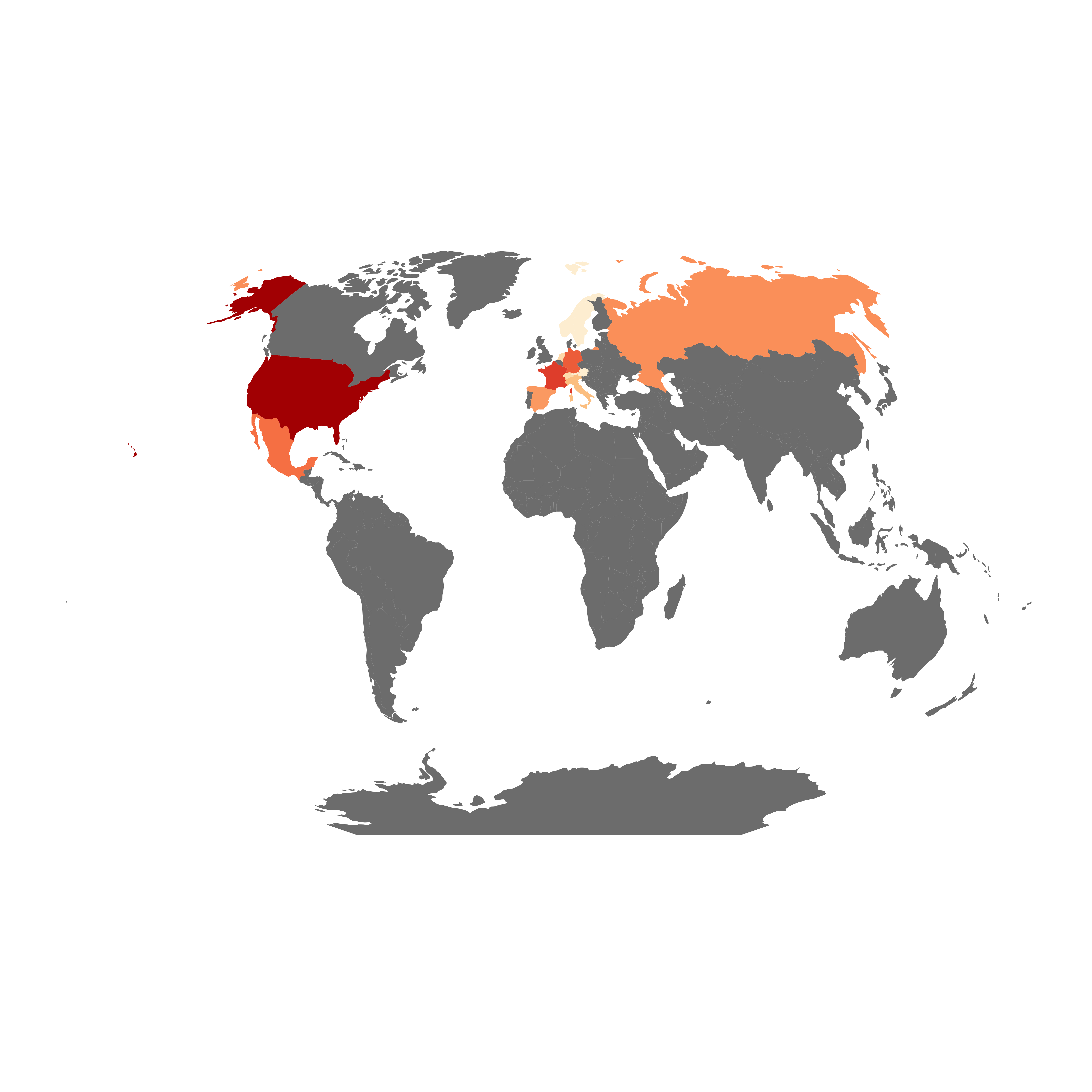

For those less interested in the code/process, I thought I would put the “final” visualization up front (for those interested in code/process, welcome! You will find it in excruciating detail in the next section). For this first crack at visualizing the data, it seemed like it made sense to show countries of origin on a world map, with shading related to how many pieces acquired in a given year were made by an artist with that nationality. Since I wanted to show how this changed over time, I broke the data into 5 year ‘chunks’ - so the chunk “1931-1935” represents the acquisitions made by the museum in the early 30s, the chunk 1936-1940 represents the same but for the late 30s, and so on. And because I am a child of the internet age, I wanted to make it a GIF.

Now this may go a bit fast, but generally, what you can see (besides the fact that the vast majority of acquisitions in every period are from American artists), is that the MoMA started to acquire more art from Latin American artists starting in the late 1930s, and that in the 1960s, started acquiring much more art from countries in Asia. It’s not really until the 2000s that MoMA started acquiring meaningful amounts of art from any countries in Africa, and even then, the numbers are fairly limited.

There are quite a few more notes about the process and the data below, but generally, I think this visualization approach, while it looks cool, is actually a bit hard to follow. I don’t know that we need this level of detail, for one, and the point that it’s trying to make is a bit lost. In future posts, I’m going to explore some less fancy ways to show some of the same trends; for now, all of you code lovers out there see below:

Struggling With the Data

As you’ll see, this data was a pain to work with, which led me to load/install so many packages that I’m not actually sure which ones were even necessary in the end. I’m putting them all here, for completeness’ sake, but it’s possibly you don’t need all of them - at some point I’ll try to go through and remove the unecessary ones.

########################

# SET-UP

#######################

library(readr)

library(stringr)

library(gdata)

library(plyr)

library(maps)

library(maptools)

library(rgdal)

library(ggplot2)

library(broom)

library(animation)

library(RCurl)

library(anytime)

gpclibPermit() # This is a command that needs to be run to get rgdal to work properly (at least for me)The data is available as a csv, so I just load it directly from GitHub. The benefit of this is that as MoMA improves the data, the results might improve; the disadvantage is that if they change any of their variable names all of my code might break. C’est la vie, and all that.

# Load data. I have to use the Rcurl package here because R doesn't like HTTPS links

my.url<- getURL("https://media.githubusercontent.com/media/MuseumofModernArt/collection/master/Artworks.csv")

df <- read.csv(text=my.url)The MoMA data has nationality as a field already (!) which I got very excited about at first. But then I looked at it.

head(df[,4:5])## ArtistBio Nationality

## 1 (Austrian, 1841â\u0080\u00931918) (Austrian)

## 2 (French, born 1944) (French)

## 3 (Austrian, 1876â\u0080\u00931957) (Austrian)

## 4 (French and Swiss, born Switzerland 1944) ()

## 5 (Austrian, 1876â\u0080\u00931957) (Austrian)

## 6 (French and Swiss, born Switzerland 1944) ()Just from these top rows, it’s clear it has issues. In particular, it seemed to have problems with cases where the artists had dual nationalities. In some other cases (not shown here), it just chose one, seemingly arbitrarily, which I didn’t want either.

The artist bio field seemed like a better shot, though a bit harder to work with. The dates were a bit garbled but I wasn’t interested in those, and it seemed like it would be possible to extract the nationalities. What’s more, there were only 4,656 pieces with missing data, which isn’t bad out of 131,266 pieces overall (4%).

To actually get the nationalities out of the artist bio field, however, I had to use the grep function, which I had never used before (as will be crystal clear from the code below). The rough idea of the code is to cycle through a list of nationalities, and for each, extract the pieces which had that nationality mentioned in the artist bio section. I would then end up with a set of dataframes (one for each nationality), with all of the pieces that were created by an artist of that nationality. A key thing to note here is that this means that pieces are double counted if the artists have dual nationalities or if there are multiple artists from different countries. I actually decided this is what I wanted – if a piece is by an artist who is both French and Algerian, I don’t want to choose which country the piece will be attributed to – but it is something to keep in mind when interpreting the results. It’s also a good example of the kinds of substantive data choices that you have to make even for a simple analysis, which aren’t often as well documented as they should be in the academic literature (which is why code sharing is great!).

The code below does what I just described; it isn’t the most elegant, so if anyone has better ideas for how to do this, I would love to hear.

# read in table of nationalities

# (this is just an excel file with country names in one column, and nationality names in the second)

my.url <- getURL("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/imaddowzimet/Misc/master/Nationalities%20Country%20Crosswalk.csv")

nationalities <- read.csv(text=my.url, header=FALSE)

# the code below creates a list of data frames, one for each nationality, which contain all the pieces of artists of that nationality

# (artists with dual or multiple nationalities will appear in multiple data frames, which is what we want for now.)

df$Nationality <- NA # drop the nationality info that we are not using

numrows <- dim(nationalities)[1] # count nationalities

mynationalitysubsets <- list() # initialize list

for (i in 1:numrows) { # for each nationality

# check the "artist bio" section, and if it has a nationality that matches the nationality list, select it for the dataset

mynationalitysubsets[[i]] <-

df[grep(paste0(nationalities$V2[i]," ","|",nationalities$V2[i],","),df$ArtistBio),]

# if the dataset we just created is not empty

if (nrow(mynationalitysubsets[[i]])>0) {

# then create a variable "nationality" with the corresponding nationality

mynationalitysubsets[[i]]$Nationality <- as.character(nationalities$V2[i])

}

}

# We now have a list of datasets; one for each nationality.

# Now we are going to append all of the datasets into one giant one

dfFinal <- mynationalitysubsets[[1]] # assign first dataset to dfFinal

for (i in 2:numrows) {

dfFinal <- rbind(dfFinal,mynationalitysubsets[[i]] ) # append the rest

}So now I have one big dataset, with each piece either taking up one or multiple rows (in the case of dual nationalities/multiple artists). As a gut check, I can look at the N of this new dataset:

dim(dfFinal)[1]## [1] 124934Hmm. I started out with an N of 131,266, of which 4,656 had missing data for the artists bio field. 131,266 - 4,656 = 126,610, but then I know some pieces are double counted, so I should have more than that number. Instead, I have less. Probably what happened is that some of the artist’s bio fields had information but not valid nationalities, so they weren’t initially captured in my missing data check; since I don’t have a good way to impute these though, and the drop in size doesn’t seem alarming, I proceed onwards and upwards.

Now I have nationalities but not countries, so I need to merge those in if I want to do anything with maps.

##Merge in country names

nationalities <- rename(nationalities, c("V2"="Nationality","V1"="Country" )) # rename variables in nationality/country list

nationalities <- nationalities[!duplicated(nationalities$Nationality), ] # remove duplicate nationalities

nationalities$Country[nationalities$Country=="Dominica"] <- "Dominican Republic" # Fix an error in spreadsheet (oops!)

orig.length<- dim(dfFinal) # This will be used to make sure the join is working correctly

dfFinal <- join(dfFinal, nationalities, by='Nationality', type='left', match='all') # Merge datasets

orig.length[1]== dim(dfFinal)[1] # Check we didn't lose any rows

dfFinal$Country<- as.factor(dfFinal$Country) # change nationality to factor variableSo now we can actually start looking at what we have! I know that eventually I want to look at artists’ country of origin by date of acquisition, but I tend to always just want to do a one way tabulation of my variable to get a sense of what I have, and make sure that I haven’t made some horrible, horrible mistake.

# create a table of overall counts by nationality

mytable <- table(dfFinal$Country) # create table of counts

mytable # print table of counts! This is going to be wayyy too big.##

## Afghanistan Albania Algeria

## 1 24 6

## Andorra Angola Argentina

## 0 1 0

## Armenia Australia Austria

## 2 248 1107

## Azerbaijan Bahamas, The Bahrain

## 1 3 0

## Bangladesh Barbados Belarus

## 0 0 0

## Belgium Belize Benin

## 1507 0 0

## Bhutan Bolivia Bosnia and Herzegovina

## 0 4 10

## Botswana Brazil Brunei

## 0 732 0

## Bulgaria Burkina Faso Burundi

## 11 0 0

## Cambodia Cameroon Canada

## 8 13 836

## Cape Verde Islands Chad Chile

## 0 0 534

## China Colombia Congo, Dem. Rep.

## 211 721 3

## Costa Rica Croatia Cuba

## 64 157 190

## Cyprus Czech Republic Denmark

## 1 908 623

## Djibouti Dominican Republic Ecuador

## 0 0 0

## Egypt, Arab Rep. El Salvador Eritrea

## 59 0 0

## Estonia Ethiopia Fiji

## 1 1 0

## Finland France Gabon

## 231 22774 0

## Gambia, The Georgia Germany

## 0 17 10018

## Ghana Greece Grenada

## 4 54 0

## Guatemala Guinea Guyana

## 68 0 1

## Haiti Honduras Hungary

## 17 0 776

## Iceland India Indonesia

## 51 100 2

## Iran, Islamic Rep. Iraq Ireland

## 45 4 52

## Italy Jamaica Japan

## 2938 0 2719

## Jordan Kazakhstan Kenya

## 0 0 12

## Korea, Dem. Rep. Korea, Rep. Kuwait

## 0 0 1

## Lao PDR Latvia Lebanon

## 0 73 50

## Liberia Libya Lithuania

## 0 0 73

## Macedonia, FYR Madagascar Malawi

## 1 0 0

## Malaysia Maldives Mali

## 7 0 10

## Malta Mauritania Mauritius

## 0 2 0

## Mexico Moldova Monaco

## 1305 0 0

## Mongolia Montenegro Morocco

## 0 0 5

## Mozambique Myanmar Namibia

## 1 0 1

## Nepal Netherlands Nicaragua

## 0 1659 1

## Niger Nigeria Norway

## 0 10 183

## Oman Pakistan Panama

## 0 47 4

## Papua New Guinea Paraguay Peru

## 0 3 107

## Philippines Poland Portugal

## 0 488 169

## Qatar Romania Russian Federation

## 0 71 1861

## Rwanda Saudi Arabia Senegal

## 1 1 3

## Serbia Seychelles, the Sierra Leone

## 15 0 0

## Singapore Slovak Republic Slovenia

## 2 77 27

## Somalia South Africa Spain

## 0 394 3118

## Sri Lanka Sudan Suriname

## 0 2 0

## Swaziland Sweden Switzerland

## 0 457 2325

## Syrian Arab Republic Taiwan Tajikistan

## 1 8 1

## Tanzania Thailand Togo

## 1 33 0

## Tunisia Turkey Turkmenistan

## 14 55 0

## Tuvalu Uganda Ukraine

## 0 1 130

## United Kingdom United States of America Uruguay

## 5991 57611 68

## Uzbekistan Vanuatu Venezuela, RB

## 0 0 415

## Vietnam Western Samoa Yemen, Rep.

## 7 0 0

## Yugoslavia Zambia Zimbabwe

## 159 0 15So already we can tell we have a problem (aside from how gigantic and unwieldy this table is). Almost half of the pieces are from the US, and the proportion of pieces from most other countries are so small that they are going to be impossible to put on any kind of meaningful scale. Luckily, the solution here is simple, which is that we can transform the variable, and plot the counts on a log scale instead. This has the effect of compressing the distribution; we just need to remember that each one unit increase in the logged count is an exponential increase in the raw count - so unlike a rearview mirror, distances are bigger than they appear. For this case, when we are just mapping values, this kind of logged outcome isn’t a huge deal in my opinion - it will still give you an idea of the general trend, and is actually a nice way to look at change over time - but for other types of visualizations, it could be misleading or hard to interpret (something I’ll maybe get into in another post). I’m actually going to log this outcome in a later part of the code, because it’s a bit easier to do there, but I wanted to include this as a flag that it is always important to look at some simple tabulations, if possible, before getting to more complicated visualizations.

I said I wanted to look at this over time, so I need to work a bit with the date acquired variable. The code below first converts the variable from string to date format (using the extremely useful anytime function, which saved me even worrying about how R deals with dates), checks for missing data, and then creates five year breaks.

# convert from string to date format

dfFinal$DateAcquired <- anytime(dfFinal$DateAcquired)

# check % missing

length(dfFinal$DateAcquired[is.na(dfFinal$DateAcquired)])/length(dfFinal$DateAcquired)

# only 4% missing data which is nice- I'm OK with listwise deletion for now

# Create five year break variable

dfFinal$year <- format(dfFinal$DateAcquired, format="%Y") # Create year variable

dfFinal <- dfFinal[dfFinal$year>=1930 & dfFinal$year<=2015,] # I'm going to exclude 1929 and 2016 to get nicer breakpoints

breaks <- seq(from=1930, to=2015, by=5) # create breaks

dfFinal$fiveyear <- cut(as.numeric(dfFinal$year), breaks)

subsets<-split(dfFinal, dfFinal$fiveyear, drop=TRUE) # and break it into 17 seperate datasets -- one for each five year breakI then can actually do the mapping! You’ll need to download world shape files; I downloaded the ones I use from Natural Earth, a truly awesome site, which you can read about more here.

##################################################

# Map Data prep

#################################################

# Read in shape files

countries <- readShapePoly("//Users//isaacmaddowzimet//Desktop//Experiments//ne_110m_admin_0_countries//ne_110m_admin_0_countries.shp") # Change the file path to wherever these are saved.

# Change projection, so the world map doesn't look bizarre, and save as a new object

proj4string(countries) <- CRS("+proj=longlat")

winkel <- "+proj=wintri"

countries_winkel <- spTransform(countries, CRS(winkel))

# Add some margins to the plot

# par(mar=c(1,1,1,1))

# convert the map object to a dataframe (so ggplot can use it)

artmap <- tidy(countries_winkel, region="name_sort")

artmap <- rename(artmap, c("id"="Country")) # rename variables in nationality/country list, to make merging easier

dim(artmap)

# rename French Guiana (since it's a department of france, right now it's grouped with france, which is accurate, but makes it look like the MoMA was acquiring a whole bunch of art from South America in the early 1930s )

artmap$Country[artmap$group=="France.2"] <- "French Guiana"

# create counts by country, and merge with map dataframe

artmaplist <- list()

for (i in 1:17) {

data1 <- as.data.frame(table(subsets[[i]]$Country))

data1 <- rename(data1, c("Var1"="Country"))

artmaplist[[i]] <- join(artmap, data1, by='Country', type='left', match='all') # Merge datasets

artmaplist[[i]]$year <- i

}

# Append all of these into one dataset

artmapfull <-artmaplist[[1]]

for (i in 2:17) {

artmapfull <- rbind(artmapfull,artmaplist[[i]] )

}

# Convert frequency into log frequency (I told you I would get to this eventually)

artmapfull$logfreq <- log(artmapfull$Freq)Now I could just produce these maps individually - here’s 1931-1935:

# Map the first year, to try it out

ggplot(artmapfull[artmapfull$year==1,], aes(long, lat, group=group, fill=logfreq)) +geom_polygon() +

coord_equal() + guides(fill=FALSE) + scale_fill_distiller(palette = "OrRd", direction= 1 ) +

theme(axis.line=element_blank(),axis.text.x=element_blank(),

axis.text.y=element_blank(),axis.ticks=element_blank(),

axis.title.x=element_blank(),

axis.title.y=element_blank(),legend.position="none",

panel.background=element_blank(),panel.border=element_blank(),panel.grid.major=element_blank(),

panel.grid.minor=element_blank(),plot.background=element_blank()) But just for fun, I thought it would be nice to make a gif using the animation package. Getting this package to work is a bit involved, especially on a Mac (you have to install a program called ImageMagick, which is not as simple as it sounds; Google for details), but the code below should get you started.

But just for fun, I thought it would be nice to make a gif using the animation package. Getting this package to work is a bit involved, especially on a Mac (you have to install a program called ImageMagick, which is not as simple as it sounds; Google for details), but the code below should get you started.

# Create list of years (for label)

years <- c("1931-1935", "1936-1940", "1941-1945", "1946-1950", "1951-1955", "1956-1960", "1961-1965", "1966-1970",

"1971-1975", "1976-1980","1981-1985", "1986-1990","1991-1995", "1996-2000", "2001-2005", "2006-2010", "2011-2015")

library(animation)

ani.options(interval=1.5, ani.width = 900, ani.height= 600)

saveGIF(

for (i in 1:length(years)){

g<-ggplot(artmapfull[artmapfull$year==i,], aes(long, lat, group=group, fill=logfreq)) +geom_polygon() +

coord_equal() + guides(fill=FALSE) + scale_fill_distiller(palette = "OrRd", direction= 1 ) +

ggtitle(paste("Permanent collection acquisitions by country of origin:", years[i]))+

theme(axis.line=element_blank(),axis.text.x=element_blank(),

axis.text.y=element_blank(),axis.ticks=element_blank(),

axis.title.x=element_blank(),

axis.title.y=element_blank(),legend.position="none",

panel.background=element_blank(),panel.border=element_blank(),panel.grid.major=element_blank(),

panel.grid.minor=element_blank(),plot.background=element_blank(),plot.title = element_text(hjust = 0.5))

print(g)

}

)